Nestled between strategy and production, content administration provides the necessary legal, budgetary, structural, and forecasting functions for content of all types to succeed in corporate environments.

Ten years ago, I pivoted careers from creating content at a publishing and events company to developing strategies for SEO content at a performance marketing agency. The shift in business models was a bit of a shock: our agency content team focused solely on optimizing text and making suggestions for production. We had no staff graphic designer or creative director. Our few content production processes included spell check but no higher-level editorial inquiry into the ideas and meaning we suggested via the content. We didn’t yet have a human proofreader. Our optimizations didn’t even go through a line edit, one of the most standard editorial processes in publishing.

Mostly, we’d suggest different types, publishing cadences, and light optimizations as strategy and leave the rest of the creation and management process to the client. At the time, that was enough work to command plenty of new business from established corporations and sustain the SEO content department.

But it was professionally confusing, especially when compared with my previous career experiences. I’d spent my first professional decade in and around the publishing industry, where my roles mostly focused solely on the creation, editing, and organization of text content.

Whether I was at a legacy book publishing house like Houghton Mifflin or a startup hyperlocal history publisher, the sales, marketing, operations, or commissioning editorial departments took care of the business side of things. I'd collaborate with designers on making the high quality, trustworthy, and readable. The only time I experienced much of the business side of publishing was in a well-rounded summer internship program at HarperCollins, where I spent two week sessions in five different company departments. But even then, my exposure to the sales and marketing teams was minimal, since my interest was clearly in editorial.

My previous employers in publishing had staff devoted to the intricacies of intellectual property rights, and their business models separated revenue generation from production quality. At the startup history publisher, I technically worked alongside the sales and marketing team — there were only about 15 of us total, so we all lunched together — but our roles were separate. The editorial team had nothing to do with revenue generation or results beyond production quotas.

But the performance marketing agency, another startup with a larger staff, had minimal knowledge of established media production practices. We didn’t have intellectual property lawyers or even a human resources department. We were mostly making suggestions based on our professional experience and SEO best practices. As I’ve written before, creative suggestions were not valued unless they could be directly tied to performance or business impact.

After a meme image attracted a cease and desist from a legal copyright troll, I drew from my single media law class and created a presentation on why we couldn’t just download any image from the internet and tell our clients they could use it in their brand social media channels. Creative Commons licenses were now required. It slowed things down. Made things challenging. We scaled back any of the few production promises we made to clients. We could only suggest and strategize, providing strategic oversight but never executional support.

That meant that we sold many content strategies that clients never implemented. Because as the strategic agency, we were never responsible for the administrative or production realities of the content. We could optimize, distribute, and measure, but not create or implement our suggestions. Our clients had to secure the budgets and the resources for all our grand strategic dreams, and it turned out that all the best-laid strategies of SEOs and content professionals oft get quite expensive and resource-intensive.

How established media companies and tech startups differ, and why content suffers

The performance marketing agency was similar to so many digital marketing, web development, and software as a service startups, who have all the tools and skills to strategize for brilliant content and understand algorithmic distribution, but not to make the content itself. Sometimes startups will hire a single eager junior writer responsible for developing all the content. Then they balk when the writer can only produce three mediocre blog posts per week, not the eight recommended by the Google search on “how much content should we create?” The writer loves the tech company’s employment perks but is burned out on writing, editing, researching, ad nauseam.

When a tech company looks into building an editorial department that can handle higher quality or output, something more in line with an established media production company’s process, they back away, usually from sticker shock. Sure, they want to publish really great content, but they don’t want to pay for really great content.

It’s what I see as the fundamental disconnect between digital-first content and legacy media companies: digital-first companies believe they can hack their way around or disrupt the realities of human content production. Performance-oriented digital marketing and content companies will often hire senior editors with a background in journalism, only to find that the journalist’s honed skills in fact-checking and editorial quality control can be an impediment to productivity and, thus, revenue generation. The company doesn’t scope for the journalist’s actual skills. And the journalist will back away from learning about the business requirements because their professional education insisted that business and content were separate endeavors; or push back on audience research, suggesting that the audience’s needs were secondary to the production of quality information or news.

Legacy media and tech-first startups operate on starkly different business models. They have different workflows and administrative expectations, as well as different work environments. And the people who want to develop great content are often caught trying to balance what they learned was a best practice in school or from their previous employers with the contrasting expectations of their audience or, worse, the wildly out-of-alignment assumptions of their current employers.

The disconnect is why generative artificial intelligence is so appealing to the people who look at a Rothko and think, “I coulda painted that”: they don’t acknowledge the difference between the end product and creative production. They don’t consider how often the AI is wrong or alienates their established audience, as long as its content produces return on investment.

But, as with the New York Times’ copyright suit against OpenAI, rationalizing that long-established intellectual property laws don't apply to your content generation business can be thorny and expensive, if not outright illegal. And as publishers who try to hack their way around paying people fair salaries will eventually realize, keeping humans in the loop and planning for editorial processes will likely produce a higher quality and more lucrative product overall. At least, I hope that's the outcome.

What is content administration? It’s more than governance

In the early days of defining digital content strategy, shoehorning the entire administrative process into the word “governance” was sufficient. But governance is so much more than “who is in charge of the content?” Businesses that do not adequately scope for the costs of executing a strategy and the real-world requirements of sales and revenue generation in digital publishing often find content to be wildly unprofitable. They nix their content departments or the entire business when the investments don’t return as planned.

In a functional business, “governance” covers many non-content-oriented administrative skills, like budgeting, forecasting, resource management, legal requirements, vendor selection, and service design. Especially with the recent advances of both the creator economy and generative AI, the realities of governance in digital content strategy should be reevaluated and organized more in line with established media industries. Established media industries plan for the complexities of governance, as well as risk management and revenue generation, in their administrative and operations departments.

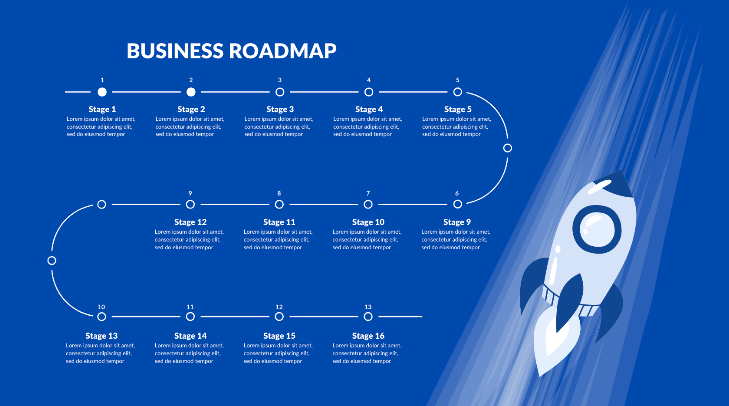

In the Content Technologist Approach, content administration determines who gets the work done, how it’s paid for, and what impact it’s expected to have on the business. The administration phase is nestled between strategy and production, designed to set expectations so both executives and creative departments are aligned. Content administration covers the following skills and responsibilities as they relate to a business’ content production:

- Project management, workflows, and timelines

- Budgeting, forecasting, and monetization

- Contracts and legal needs

- Client-side vs vendor-side created content

- Vendor and tool selection

- Service design and team structure

- Sales, scoping, and productization

- Understanding who is in charge of and responsible for content production vs. distribution vs. community management

When I outline content administration, I connect it most closely to the entertainment industry’s role of the line producer. A line producer is responsible for reading through the entire script, line by line, and determining what is or is not possible, given the production’s budget and time constraints. The screenplay may call for a realistic-looking cat character who talks and sings and dances, but if the production doesn’t have a budget for a ridiculously talented cat actor, or to hire an animation studio to fabricate a believable cat, the line producer will likely send it back for a rewrite. Can the cat character be reworked as a remarkably clever human friend?

In book publishing, the commissioning editor takes a similar role, responsible for the profit and loss of the projects they commission: if we make a budget for a presumably successful creative project, what are the production requirements needed to make our money back? Who is the intended audience, or total addressable market?

In print periodical publications, managing editors own the budgets, deadlines, communications processes, and resource allocations needed to make each issue successful and lucrative. The editor-in-chief ideally takes on the executive strategic oversight of whether the content meets the audience’s needs.

And in established creative development and advertising agencies, the project or resource managers handle most of the administration. If our client has a specific budget, what are the human resources we need and the hours we need to allocate to make it profitable? How many Don Drapers and Roger Sterlings do we need to throw at the project to win continued business?

In companies where content programs are most successful, more senior members in the content department collaborate and weigh in on the administrative process. They work with others on evaluating the effort and impact of what they intend to produce, understanding that resources are often limited. In agencies, content or strategy directors work with project and account managers on scoping, selling, and budgeting. If the client does not have in-house resources to create content recommended for their website, they suggest or partner with vendors who can help.

In enterprise businesses, the digital strategy department collaborates with established public relations, marketing, and other content and communications roles to align expectations and reality. And in startups, the best content managers adapt to understanding not only content production practices, but also service development, budgeting, user experience expectations, and algorithmic distribution. They don’t overstep their role, but they’re willing to understand how their decisions support and affect others in the business.

Whether a business is developing content for marketing, customer service, product usability, or audience growth, publishing content is quite risky, especially if algorithmic and audience expectations aren't aligned with budgetary and business realities. Everybody wants to be an expert in the fun, creative part of developing content, but without proper administration, fun and creative become expensive and untenable. Although they’re taught as anathema in some professional circles, the boring but necessary practices of content administration reduce risk. In publishing, there are no guaranteed returns on investment, but the administration processes anticipate the requirements for content to be successful beyond its initial creation and quality.

Content has a business function. Administration ensures content is profitable.

Hand-picked related content